Illinois opened the new fiscal year with a near clean slate on bill payments and $1 billion in its once-barren rainy day fund, but the state’s latest financial results offer a contrast that underscores the weight of pension and long-term debts on the state’s balance sheet as viewed through an accounting lens.

The near-term picture has helped garner a round of rating upgrades as the state has used federal COVID-19 relief and surplus tax collections to make headway on several fiscal fronts and trim an ongoing general fund gap.

The short-term snapshot of the state’s day-to-day fiscal condition — the general fund — improved in fiscal 2021. The state still recorded a deficit for the 12th consecutive year, but it was trimmed by $3.3 billion to negative $3.1 billion. It had hit a high of $14.6 billion in 2017 due to the state’s two-year budget impasse.

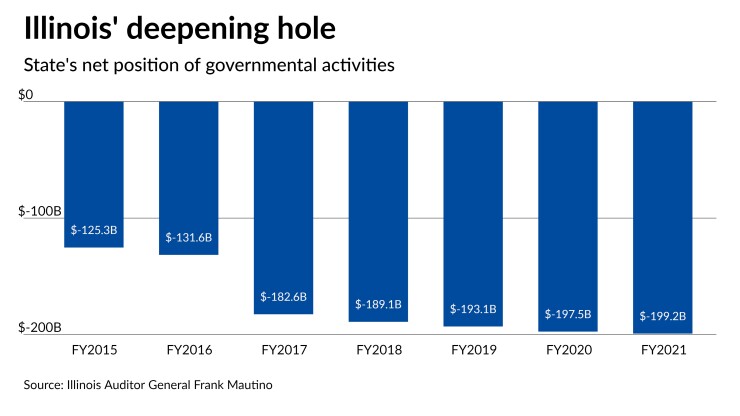

But long-term obligations sunk further into the red in fiscal 2021, highlighting the state’s vulnerability to economic swings that impact tax collections and pension fund investment returns.

The net position of governmental activities — which provides a deeper view of the state’s assets measured against obligations — worsened by $1.7 billion, bringing the gap to $199.2 billion, the worst among states that had released their fiscal 2021 audits by June 8, according to state Auditor General Frank Mautino’s report. “Over time, increases and decreases in net position measure whether the state’s financial position is improving or deteriorating,” according to the audit.

Some positive news is buried in that number, as the deficit worsened by just $1.7 billion compared to at least $4 billion in each of the previous two fiscal years.

“We’ve made progress mostly on the short end” thanks to the federal infusion of COVID-19 aid and economic recovery that boosted tax collections, said Richard Ciccarone, president of Merritt Research Services. “The state took those additional revenues” and used them to make progress in tackling liabilities.

The state needs to go much further if it’s to truly achieve long-term stability, and the current progress offers an opportunity for action on the most burdensome factor — pensions and retiree healthcare. “By shoring up the short-term it gives you the freedom to put all your big guns on the long- term problem and that’s what we want to see them do,” he said. “We’ve stabilized the ship, but the ship has some real weaknesses in the hull in the retirement area. We really need a long-term solution.”

The state’s current unfunded tab totals $139.9 billion for a system just 42.4% funded. The state faces a tough road on any pension or retiree healthcare reforms with limited options beyond pouring more funding into the system as the state constitution bans benefit cuts.

Current conditions

Gov. J.B. Pritzker, Comptroller Susana Mendoza and other officials last week pointed to metrics that should drive improvements reported in the future fiscal 2022 audit as the state heads into the new fiscal year.

“A significant surplus and a zero-day payment cycle mean that our schools are funded, our roads are being rebuilt, and our healthcare providers are paid on time — and Illinois taxpayers are no longer dealing with hundreds of millions of dollars in interest payments,” Pritzker, a Democrat who faces Republican challenger state Sen. Darren Bailey in the November general election, said last week.

The state ended fiscal 2022 with just $1.8 billion in bills — down from $3 billion a year ago — a low in more than a decade and Mendoza said bills are now being paid immediately for the first time in recent memory compared to a delay of 210 days during the state’s two-year budget impasse in 2016.

“Today’s fiscal report means that Illinois is better poised to face upcoming challenges to state finances as the nation experiences record levels of inflation,” Mendoza said.

Overdue bills, which are closely tracked by investors and rating agencies as a sign of the state’s liquidity, hit a high of more than $16 billion in 2017.

The comptroller’s officer earlier in June made a $430 million deposit into the rainy day fund, bringing it to $751 million. The state’s fiscal 2023 budget allocates additional funds to raise it to $1 billion, lean by recommended practices but a record level for Illinois as it held just $60,000 when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The state closed out fiscal 2021 with a balance of $5.7 million in the fund, according to the 2021 audit.

The remaining $200 million of the $500 million in additional funds directed to pension funds from state surplus revenues was made July 1. The supplemental funding is expected to trim liabilities by $1.8 billion.

The state’s last pension system audited reports, which will factor into the state’s fiscal 2022 audit, showed a drop in unfunded liabilities. But the potential for weaker returns grew in recent months, which would drive up the unfunded tab, but would not be felt until the following year’s audited results.

The various actions on the surplus, pension funding, and paying down bills helped win a round of upgrades from Fitch Ratings, Moody’s Investors Service, and S&P Global Ratings that put the state’s ratings at BBB-plus, Baa1 and BBB-plus, respectively, but reaching the single-A category will require a heavier lift on metrics, analysts have said.

Fiscal 2021

In fiscal 2021, the state’s capital assets totaled $23.3 billion covering land, buildings, equipment, infrastructure, and other items with estimated useful lives of greater than one year. The state’s long-term liabilities were led by a $151.9 net pension liability, other postemployment benefits liability for healthcare totaling $56.7 billion, and bonds and notes payable of $32.4 billion, including $29.6 billion of long-term bonds.

The state’s assets increased $2.4 billion while liabilities rose $6.9 billion with net pension liabilities increasing $8.5 billion. OPEB liabilities decreased $1.9 billion. Short-term notes payable increased $2.8 billion due to the increase in borrowing by the Unemployment Compensation Trust Fund. That tab is partially be repaid with some of the state’s $8 billion share of America Rescue Plan Act funds.

In the outlook section, the audit warns: “The state continues to show an inability to generate sufficient cash from its current revenue structure to pay operating expenditures on a timely basis” with the state’s two largest revenue sources, income tax and sales tax, especially susceptible to economic swings.

The pandemic’s potential lingering impacts and economic uncertainty pose risks that — along with the accumulated general fund gap, growth in the net pension liability and OPEB liability, and bond ratings — could “impact the state’s ability to access credit markets to pay operational expenditures more timely and may increase interest costs of those borrowings,” the audit warns.

Illinois counts itself among only nine states with a negative net position of governmental activities and holds the distinction of being the worst among the group, with New Jersey trailing close behind at $196.5 billion. Arkansas carries the strongest surplus at a positive $88.8 billion.

That’s improved from fiscal 2020 when among the nation’s states and the District of Columbia, 12 ended the year in negative territory, according to a chart published by Mautino.

The fiscal 2021 comparison excluded Arizona, California, Iowa, Nevada, and Wyoming, where audits were not available as of June 8, according to the auditor general’s report.

The timing of the audit also offered a mixed bag. It remained tardy coming nearly one year after the close of the fiscal year while a 120-day time frame is the Government Finance Officers Association’s recommended practice.

But it was improved from the fiscal 2020 release date in late August. The state lagged most others in reporting the 2021 audit but it did beat a handful of states while it has in past years been the last or near last to publish.

The comptroller says the office must wait on the auditor general’s office to complete its work while the auditor general says delays in state reporting are to blame. Mendoza released interim audit results in January as the formal report was pending.

System updates under a multi-year implementation of an Enterprise Resource Planning system and grant reporting are expected to eventually result in more-timely financial reporting.

In addition to upgrades, the state’s healthier near-term picture drove secondary trading spreads to lows not seen in recent memory late last year and early in 2022. Market turmoil amid rising inflation and Federal Reserve rate hikes have erased much of the improvement.

The state’s 10-year and 25-year were at 63 bp and 66 bp spreads, respectively, to start the year. They widened to 96/99 in early March, grew to 123/130 in early May, and were at 132/153 last week.