China’s crackdown on foreign investors and domestic property speculation has prompted many international investors to head for the exits. Ray Dalio is not among them.

Instead, the founder of the $140bn US hedge fund Bridgewater Associates and one of the most prominent foreign investors in the country, said he has spoken directly to officials from the Chinese Communist party in the past week, and been encouraged by what he heard.

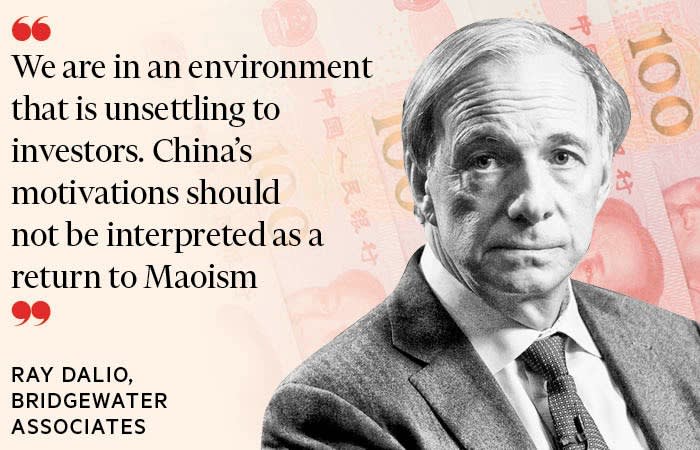

“At this stage I’m assured that this doesn’t mean foreigners and foreign investors are not welcome,” said the 72-year-old, who first visited China 37 years ago. “We are in an environment that is unsettling to investors”, conceded Dalio. But “China’s motivations should not be interpreted as a return to Maoism”, he said in an interview with the Financial Times.

Beijing’s regulatory blows, targeting sectors from video games to education, have wiped more than $1tn of market value from Chinese equities since their recent peak in mid-February.

Goldman Sachs estimates that a further $3.2tn of market capitalisation could be exposed to further regulatory uncertainty — roughly a sixth of the market cap of all Chinese listed companies.

But Dalio says Beijing is seeking the “common prosperity” set out in President Xi Jinping’s 14th five-year plan in March. It wants to correct a period when capitalism raised living standards but also created a “large wealth gap” and “too much debt”, he said.

This week, investors in an offshore bond issued by property developer Evergrande have felt the sharp end of Beijing’s interventions. By Friday afternoon, they had still yet to receive a high-stakes interest payment that had fallen due the previous day.

The world’s most indebted property group has come under pressure as authorities have cracked down on excessive debt in the sector. It has a 30-day grace period before any failure to pay officially results in a default. A missed payment would kick off the biggest restructuring in China’s financial history, in a sector that accounts for nearly a third of the country’s economy.

Renowned short seller Jim Chanos warned this week that Evergrande’s crisis could be “far worse” for investors in China than a “Lehman-type” systemic crisis because it points to the end of the country’s property-driven growth model. China would need to find “new growth drivers”, he added, “or downshift somewhat semi-permanently into a lower level of growth”.

Others were more sanguine, maintaining that government intervention in China is nothing new and does not derail longer-term structural trends, such as an emerging middle class of consumers.

“It would be extreme and wrong-headed to regard China as uninvestable,” said Fred Hu, chair and chief executive of Primavera Capital Group, and former head of China at Goldman Sachs. “In the same way, no one could credibly claim Europe is uninvestable just because of the euro debt and banking crisis or Brexit, or US off limits because of the subprime debt crisis.”

However, it would be “enormously helpful,” Hu added, “if the Chinese authorities could try to improve communications with investors and provide a greater degree of policy consistency and predictability”.

The Evergrande crisis and Beijing’s curbs have roiled markets in recent months. But many foreign investors in China insist that their long-term time horizons help them ride out short-term jitters.

“Compared with the US, Europe and Japan, I think of China as an economic adolescent . . . tempestuous and volatile but its best decades are ahead,” said Howard Marks, co-founder of distressed asset manager Oaktree Capital Management.

“China is working on growing as a financial player on the international stage within the context of their ideology”, Marks added. “If they act in an unpalatable way towards outsiders, they won’t progress the way they want to.”

‘Why would you invest in China?’

An abrupt and wide-ranging regulatory crackdown began last November when the $37bn blockbuster initial public offering of Chinese payments group Ant was torpedoed at the eleventh hour by Beijing regulators. Next came anti-monopoly and data security measures against some of China’s largest tech companies, including ecommerce group Alibaba, takeaway delivery and lifestyle services platform Meituan, and ride-hail app Didi Chuxing — formerly popular picks in the global investor community.

As Xi tries to reshape the country’s cultural and business landscape as part of a “common prosperity” drive, Beijing has imposed strict limits on the amount of time young people can play video games. It has also banned the for-profit education sector and stepped up criticism of the cosmetic surgery industry.

After the last-minute cancellation of the Ant IPO, Ben Rogoff, London-based director of Polar Capital’s technology funds, cut its positions in Alibaba and Tencent. “We’ve missed Chinese stocks in the past, but that’s fine because the political risk is higher than perceived,” said Rogoff, whose funds are now even more underweight China relative to their benchmark.

“In tech there are genuinely thousands of stocks in our investable universe”, Rogoff added. “I can build a portfolio with a 20-25 per cent growth trajectory with little direct exposure to China.”

Hedge fund manager Kyle Bass stopped investing in China 12 years ago. After studying the country’s banking system and the strategy of policy officials. “I decided it was a market that I would never invest in,” said the founder of Dallas-based Hayman Capital Management.

“A question for investors is why would you invest in China given all the risks. There is no rule of law, there is no fiduciary duty towards investors, and no appropriate level of auditing for their companies.”

“China is rule by law but not rule of law,” added short seller Carson Block, Texas-based founder of Muddy Waters Research. “I’m not going to be long China because the numbers are not trustworthy and nothing about it is trustworthy.”

But other investors view Xi’s “common prosperity” drive as an opportunity to back sectors aligned with the government’s aims of building a fairer and more productive economy.

In the view of these more bullish investors, Xi is seeking to rebalance the economy towards consumption-driven growth, while addressing inequality and supporting industries such as renewable energy, green manufacturing, healthcare, software, artificial intelligence and those that drive the ‘Made in China’ narrative. The trade war with the US has accentuated the need to build a domestic supply chain and reduce dependence on imports from the US.

At any rate, it helps to be aligned with Beijing’s agenda: “The lesson of investing in China is to be on the right side of government policy,” said Justin Thomson, head of international equity at T Rowe Price.

Additional reporting by Leo Lewis in Tokyo