In March 2012, Andrew Left, a short-seller based in the US, received a mysterious package with no return address. Inside, a 68-page document made explosive claims about a Chinese property developer that was then little-known outside of its home market.

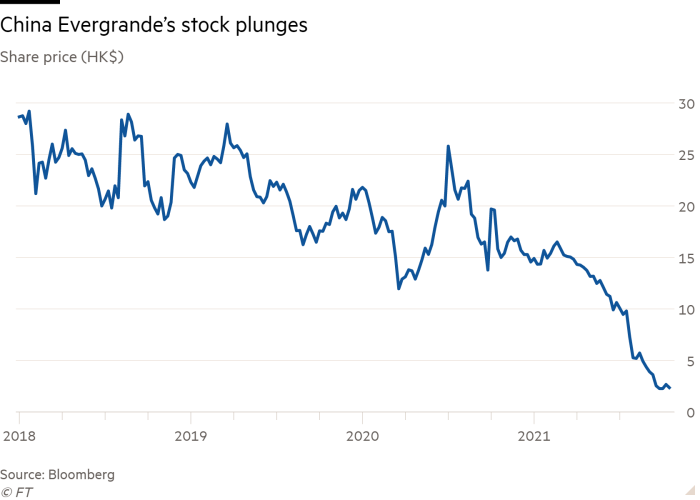

Left’s subsequent report on Hong Kong-listed Evergrande Real Estate Group, which alleged it was “insolvent” and “will be severely challenged from a liquidity perspective”, earned him $1.6m in profits after a share price plunge, but a lengthy court case brought by the territory’s market regulator cost him much more.

“I went pretty deep in on this,” says Left, who was found to have disseminated “false or misleading information” and banned from the territory’s financial markets. “I stopped counting the bills after $1m.”

This week, the Chinese company that has come to embody the vast debts behind the greatest urban transformation in history was finally engulfed by the crisis that sceptics had repeatedly forecast over the past decade.

Evergrande’s name on Monday flashed across trading screens from New York to London as its rapidly unfolding liquidity woes, which have mounted within China since July, burst onto global markets ahead of a Thursday interest payment deadline on one of its $20bn of US-dollar bonds. The payment had still not been made as of Friday.

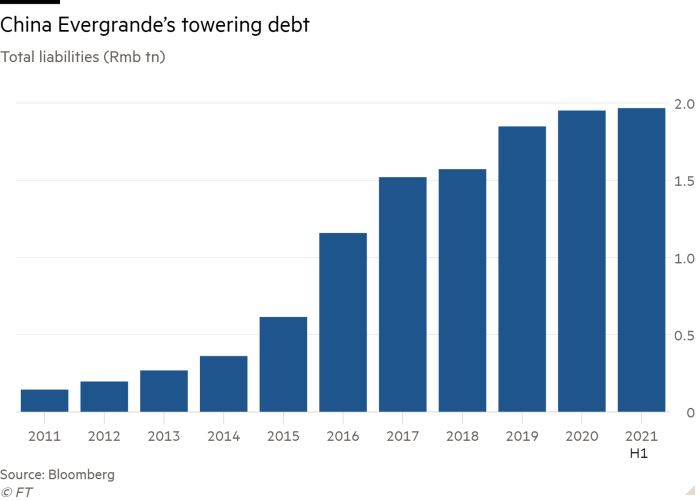

But it is the company’s $300bn in total liabilities, a largely domestic sum accrued through buying land to build residential apartments across hundreds of China’s cities and selling them before they are completed to repeat the process, that have prompted comparisons to the systemic ructions of 2008.

The fate of the company, which is widely expected to require the biggest restructuring in the China’s history whatever happens with the interest payment, has this week emerged as a crucial test case for the property sector, which has long anchored the country’s economic growth model but is now under pressure to reduce leverage after a shift in government policy.

Poker-playing billionaire

Evergrande was launched in 1996 by Hui Ka Yan, who previously worked in the steel industry, in a year where less than a third of China’s population lived in cities. When the company listed in Hong Kong in 2009 after a previous failed attempt, its shares soared 34 per cent. By 2017, when China’s urbanisation rate had climbed to 58 per cent, Hui was the country’s richest man with a fortune of $45bn and became known for playing poker with a group of fellow Hong Kong billionaires.

Like many of China’s biggest conglomerates, the company has drawn in capital from stock and bond markets in Hong Kong, the main gangplank to an otherwise largely closed off global financial system. The tribunal that sanctioned Left noted that the “great majority of Hong Kong market analysts were bullish as to Evergrande’s prospects” in 2012. As recently as last month, almost half of analysts in Hong Kong covering it still had a buy rating on the stock, which has plunged 84 per cent this year.

The pace of its growth in debt and land reserves across the border, which last year were enough to house millions of people, continually raised eyebrows. But many believed that the business was large and important enough to be able to rely on Beijing’s support.

One private equity chief executive in Hong Kong said investing in Chinese property developers — which make up a sizable chunk of the $400bn Asian high yield bond market — hinges on the “fundamental belief” that the central or local governments would never allow a “blow-up”.

“If you believe the government will always step in at the crucial point, you are going to assume greater risk,” said the person, who banned his own team from investing in Evergrande. “If you’re a bond fund manager fighting for every basis point on your bonus, that pays off each year.”

That wider belief was shaken by the unveiling of the government’s “three red lines” rules in the summer of 2020, which limited developer leverage months after a cut in interest rates prompted fears over asset bubbles.

“I think one of the key things that people have underestimated is the significant paradigm shift that the government has instigated within the property sector,” said Nish Popat, co-lead portfolio manager for the emerging markets corporate debt team at Neuberger Berman, who also noted the widespread view outside of China that the company was too big to fail. “When we spoke to our Shanghai team,” he says, “they did not believe that that was the case.”

At a time when some international funds were still buying Evergrande debt, Neuberger Berman in July exited its position because it felt “uncomfortable”. In the same month, news emerged that Rmb132m of its mainland subsidiary’s deposits at a bank in Jiangsu province had been frozen, while local authorities in Shaoyang, Hebei province, halted construction at two of its projects. Both decisions were rapidly reversed, and small relative to the size of the company, but hurt sentiment.

Evergrande warned over the risk of default in August, days after an unusual public rebuke from Beijing ordering it to reduce its debts, and blamed the effect of “negative reports” on its liquidity. Under pressure from the three red lines, the company had cut its debt from Rmb717bn at the end of last year to Rmb572bn in June. But over the same period its liabilities edged higher to Rmb1.97tn, and were by then 10 times their 2012 level.

News also began to emerge of litigation from contractors over unpaid bills, and the company was on course to face a record number of legal cases in Chinese courts, though it still made a net profit in the first half of the year. Sales on its properties almost halved from June to August and it expected deteriorating sales in September, usually a busy month.

While global markets have this week fixated on Evergrande’s liabilities, its assets have long attracted scrutiny given a focus on unused housing stock arising from China’s construction boom.

Nigel Stevenson, an analyst at GMT Research, published a report on the company in 2016 with a target price of $0 a share after visiting 40 projects across 16 cities. He noted the company had almost 400,000 car parking spaces on its balance sheet valued at $7.5bn, roughly equivalent to its entire equity base, and criticised the quality of other assets.

“These assets still need to be financed, and they’re obviously being financed at 10 per cent plus which is not sustainable long term,” he said. “Things have finally caught up with them.”

International fund managers have previously benefited from the high yields on Evergrande’s debt, in an era when swathes of the global bond market have traded at negative rates on loose Western monetary policy.

The bond with the payment due on Thursday was issued with a coupon of 8.25 per cent in 2017, and this week its price tumbled to as low as 24 cents on the dollar. In a note to clients last week, UBS, which held $300m of Evergrande bonds as of various filing dates between April and July, said they were trading “at or below typical historical recovery values”.

As expectations of a restructuring mount, some offshore investors are closely watching the company’s assets outside of China that it accumulated as it expanded beyond property, including a stake in a Hong Kong-listed electric vehicle company that is yet to sell a car.

A group of international investors have hired law firm Kirkland & Ellis and investment bank Moelis & Co to advise on a potential restructuring.

“The likelihood that Evergrande will prioritise the offshore noteholders is diminishing quickly and is extraordinarily low,” said John Han, a lawyer at US firm Kobre & Kim, who is in discussions with a number of large activist US funds that hold positions in Evergrande bonds. “The Chinese government is going to prioritise retail investors and homebuyers and domestic banks over western distressed debt funds.”

S&P, which expects a default, does not anticipate direct government involvement but expects Beijing will seek an “orderly restructuring”. Within mainland China, the future of Evergrande will be a deeply sensitive process and political test for President Xi Jinping given the involvement of ordinary citizens who have already paid for apartments. The company has 778 projects across 223 cities, and last week retail investors descended on its Shenzhen headquarters to demand their money back.

Direct spillovers to international markets are limited beyond Asian high yield bonds. But a prominent failure could hit confidence across the wider property sector, on which global commodity markets and local government finances both rely heavily. Land sales plummeted 90 per cent year-on-year at the start of September, while new home sales have also fallen sharply. Prices of new houses across the 70 biggest cities were still rising marginally year-on-year in August, however.

Andrew Left, who has never been to China and relied on the internet and company filings for his bet against the company, said he did not feel “great” watching the news unfold this week.

“I’ve never been in a situation before where people congratulate you and you’ve got nothing from it,” he said. “It’s been such a big part of [my] life for so long, and now it’s become part of financial history.”

Left’s five-year ban expires next month but he still has one question: “Are the courts going to go after all the analysts who put $40 targets on it?”

Additional reporting by Edward White in Seoul and Tom Mitchell in Singapore